Draft Climate Change Plan – Transport: A vehicle for change?

Reading Time: 14 minutes

Background

The Scottish Government published its draft Climate Change Plan (CCP) on 6 November 2025, kicking off 120 days of parliamentary scrutiny. The draft CCP covers the period 2026-2040 across three 'carbon budgets'. Carbon budgets set a legally binding cap on the maximum level of Greenhous Gas Emissions (GHG) emissions for a period of five years. In effect, a carbon budget is the amount of carbon that Scotland has available to 'spend' in a set time frame, like a personal budget for shopping.

The Scottish Government has a goal of reaching 'net zero' GHG emissions by 2045.

The approach to reducing transport related GHG emissions set out in the draft CCP is largely focused on two areas:

- Encouraging and incentivising the rapid uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), as replacements for existing petrol and diesel vehicles, with a goal of all vehicles on the road being zero emission by 2040.

- Reducing private car use by a combination of policy 'carrots', that is improving alternatives to car use such as walking, cycling, and public transport, and policy 'sticks', physical or fiscal approaches which make car use less attractive, such as road space reallocation to buses, cyclists, and pedestrians.

The draft CCP predicts zero reduction in emissions from aviation and shipping over the three carbon budgets covering 2026-2040.

This post provides background on the second of these issues, reducing private car use, and also considers issues around the decarbonisation of road freight. It goes on to summarise outcomes, policies and proposals set out in the draft CCP, challenges facing their delivery, and views expressed by stakeholders on the contents of the draft Plan.

This is an extended post, so we have added a pop-out table of contents to help with navigation.

What does the Draft Climate Change Plan say about car use reduction, the role of public transport, active travel, and freight decarbonisation?

The draft climate change plan includes two transport 'policy outcomes' that focus on car use reduction, largely through improving alternatives to travel by car. These are:

Transport Outcome 1: To address our overreliance on cars, we will create the enabling environment for reducing car use, incentivising behaviour change towards sustainable travel modes and disincentivising private car use, where these align with a just transition.

Transport Outcome 2: To support modal shift through more sustainable forms of travel, including incentivising public transport use and supporting more people to walk, wheel and cycle for everyday journeys.

A further outcome focuses specifically on freight transport:

Transport Outcome 3: To support modal shift through encouraging more freight to move by rail or water instead of road.

The delivery of these outcomes is supported by two "policy packages." These are Transport Package 2: Measures to encourage modal shift from car to active and public transport; and Transport Package 3: Measures to reduce emissions from Heavy Duty Vehicles.

The delivery of these packages is supported by one 'key policy,' which is:

- The development of a new car use reduction target and associated policy.

There are eight significant 'policies', which are:

- Continue to provide free bus travel for Scottish residents aged under 22.

- Continue the Bus Infrastructure Fund, GBP20 million was allocated to this fund in financial year 2025-26.

- Retain the commitment to active and sustainable travel investment.

- A commitment to multi-year funding for bus and active travel infrastructure programmes.

- Transport Scotland to develop and deliver bus priority measures on the trunk road network.

- Grant support for modal shift of freight from road to rail or water.

- Specific rail freight investments.

- Investment in replacement of HGV vehicles and deployment of charging infrastructure.

There are also several enabling policies, including the ongoing development of smart and integrated ticketing, work to improve public transport data collection and dissemination, and Transport Scotland working with councils and Regional Transport Partnerships to provide research, advice, and guidance.

Six of these significant policies are already in place, at least in some form, as explored below. With regards to the two other significant policies, the Scottish Government is yet to identify any specific rail freight investments or establish programmes for decarbonising road freight transport vehicles.

Car use reduction policy: The Scottish Government's draft Climate Change Plan update[1], published in December 2020, included a commitment to "reduce car kilometres by 20% by 2030", from the level recorded in 2019. That was a reduction of 7.349 billion kilometres, down to a level of car traffic last seen in 1994.

Transport Scotland published a consultation draft of A Route Map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030[2] in January 2022. This set out 32 interventions aimed at reducing car use.

Audit Scotland published a report, Sustainable transport: reducing car use[3], in January 2025 which concluded that the Scottish Government was "unlikely" to achieve the 20% reduction by 2030. The Public Audit Committee questioned the Cabinet Secretary for Transport about this report at its meeting of 23 April 2025[4], at which she announced the abandonment of the 20% target.

The Scottish Government published Achieving Car Use Reduction in Scotland: A Renewed Policy Statement[5] on 12 June 2025.

This confirmed the continuing commitment of both the Scottish Government and local authorities (represented by COSLA) to car use reduction. While the policy statement did not include a target for car use reduction it did highlight that:

The UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) in its recent Scotland's Carbon Budgets Advice for the Scottish Government indicates that Scotland would now need a 6% car use reduction by 2035 in line with its proposed meeting of carbon budgets.

It is important to note that the 6% mentioned in the Climate Change Committee advice does not refer to an actual reduction in the distance driven by car. As part of its work to understand what action needs to be taken to meet GHG reduction targets the Climate Change Committee modelled two scenarios, a 'baseline' where no decarbonisation action is taken and a 'balanced pathway' where sufficient decarbonisation action is taken to meet the carbon budget caps.

Under both scenarios, as set out in data presented by the Climate Change Committee[6], there is a predicted increase in the distance travelled by car. Under the balanced pathway, between 2025 and 2035, there is expected to be 6% fewer car miles driven than under the baseline scenario. However, even under the balanced pathway the Climate Change Committee predicts an increase in the distance driven by car from an estimated 36.51 billion kilometres in 2025 to between 38.32 and 40.55 billion kilometres in 2035.

That is a potential increase in distance driven of between 5% and 11%, bearing in mind that these balanced pathway figures already include the 6% reduction from the baseline.

The draft CCP (Annexe 2, page 33[7]) states that:

Consistent with the CCC advice, we will need to reduce annual car mileage by at least 4% by 2030 (on a 2030 'business as usual' forecast baseline).

As explained above, that is 4% fewer miles driven than predicted under the baseline scenario, rather than an actual reduction in driving. Under the balanced pathway, the Climate Change Committee predicts that the distance driven by car will grow by between 0.9 billion kilometres and 1.75 billion kilometres between 2025 and 2030.

The draft CCP goes on to state that the car use reduction target will remain under review until the publication of the final version of the Plan, with a view to setting a more ambitious target than the suggested 4% by 2030.

Using the Climate Change Committee estimates of the distance driven by car, to simply keep car use in 2030 at 2025 levels would require a reduction in car mileage predicted in the baseline scenario of between 6.5% and 8.8%.

Concessionary fares: Transport Scotland operates two national concessionary travel schemes under the provisions of the Transport (Scotland) Act 2005 and associated regulations. These are:

- Scheme for older and disabled people: Launched in April 2006, this scheme offers free travel on registered local bus services and scheduled coach services within Scotland to Scottish residents aged 60+ or to disabled residents of any age.

- Scheme for young people: Launched in January 2022, this scheme offers free travel on registered local bus services and scheduled coach services within Scotland for Scottish residents aged five to 21 years (children aged 0-4 already travel on buses for free).

As part of these schemes, bus operators are paid a proportion of the full adult fare for each concessionary traveller carried, known as the reimbursement rate.

The total amount payable to operators taking part in the scheme for older and disabled people is also subject to an annual cap, with no further payments made to any bus operator if the cap is reached.

The reimbursement rates for the national concessionary travel scheme for older and disabled people for the current fiscal year (2025-26) are 52.9% of the full adult single fare for the journey being taken, with the payment cap set at GBP215.1 million.

The reimbursement rate for the young persons' concessionary fares scheme is currently 47.9% of the full adult single fare for journeys taken by people aged 5 to 15 and 72.4% for those aged 16 to 21. The young persons' scheme is not currently subject to a payment cap.

The Scottish Budget 2026-27 has provided GBP472.8 million to support the provision of the two national concessionary travel schemes during the next financial year.

There has been a significant growth in expenditure on concessionary travel since the introduction of the scheme for older and disabled people on 1 April 2006. At constant 2025-26 prices the equivalent of GBP252,433,701 was spent on concessionary fares in 2006-07, compared with GBP472,800,000 for 2026-27 - an 87.3% real terms increase.

Much of this increase can be attributed to the introduction of free bus travel for under 22s in January 2022.

The number of concessionary journeys was on a long-term downward trend between 2006-07 and 2021-22 falling from 156 million to 137.5 million trips, when the under 22 scheme was introduced. Even so, in 2023-24 there were only 21.3 million (13.5%) more concessionary trips made than in 2006-07.

Bus infrastructure fund: The Bus Infrastructure Fund (BIF) was introduced in financial year 2025-26 with an allocation of GBP20 million. BIF funding supports the development of on-street bus infrastructure by local authorities and Regional Transport Partnerships.

The BIF replaces the Bus Partnership Fund (BPF), a GBP500 million fund launched in 2019, also to support the development of on-street bus infrastructure. The BPF was wound up in 2024 with only just GBP26.9 million (5.4% of the GBP500 million) allocated, largely to support the initial stages of project development work.

Active travel funding commitment: Transport Outcome 2, Policy 5 (annex 2, page 90) states that the Scottish Government aims to "Retain the commitment to Active and Sustainable Travel investment." It is unclear what this "commitment" relates to.

The now defunct 2021 Bute House Agreement[8] did include a commitment to "increase the proportion of Transport Scotland's budget spent on Active Travel initiatives so that by 2024-25 at least GBP320m or 10% of the total transport budget will be allocated to active travel."

Scottish Government budget documents for the years 2020-21 to 2026-27 give the following allocations for investment in active travel:

| Active travel allocation | |

| GBP226 million (including an unspecified amount for the Bus Infrastructure Fund - although it is slated to be more than in 2025-26). | |

| GBP188.7 million (includes roughly GBP23 million for 'sustainable travel' - largely accounted for by the GBP20 million bus infrastructure fund) | |

| GBP220.0 million | |

| GBP190.0 million | |

| GBP150.0 million | |

| GBP100.5 million | |

| GBP85.0 million |

It is worth noting that Audit Scotland state on page 22 of their January 2025 report "Sustainable travel: Reducing Car Use[9]" that:

Although budget allocations for active travel and sustainable transport have increased since 2019/20, the actual amounts spent have reduced.

This is accompanied by a chart showing underspends on active travel allocations in some years.

Even assuming the full GBP226 million will be spent on active travel during 2026-27, the year with the largest allocation, that would account for roughly 5.3% of the total Scottish Government transport budget for that year. That is obviously well short of the Bute House Agreement commitment to spend 10% of the total transport budget on active travel from 2024-25.

Trunk road bus priority: The 2019-20 Programme for Government[10] included a commitment to:

...begin to design a scheme next year to reallocate road space to high occupancy vehicles, such as buses, on parts of the motorway around Glasgow.

No such scheme has been delivered to date.

Freight grants: The Scottish Government provides financial support to companies wishing to develop infrastructure required to use rail or water for freight purposes through its Freight Facilities Grant scheme, and to cover increased operating costs of switching from road transport through its Mode Shift Revenue Support Scheme.

However, the sums allocated through these schemes are, in the context of the transport budget, miniscule.

With GBP1.3 million in total being allocated in Freight Facilities Grants since 2021 and even smaller amounts through the Mode Shift Revenue Support Scheme.

Scope of expected emissions reduction

As shown in the table below (figures from the CCP), the contribution to total transport emissions reduction of shifting car trips to active and sustainable travel is relatively small, reducing in importance over the years as petrol and diesel cars, vans, trucks, and buses are replaced with zero emission equivalents. Action to decarbonise freight transport, largely through the replacement of diesel engine Heavy Goods Vehicles with zero emission equivalents, accounts for around one fifth of all transport decarbonisation policy benefits.

Transport related emissions reductions produced by modal shift policies (reductions relative to CCC baseline figures)

| Measures to encourage mode shift from car to active and public transport | 0.8 MtCO2e | 0.9 MtCO2e | 0.9 MtCO2e |

| Total CCP transport policy related emission reductions | 7.5 MtCO2e | 17.8 MtCO2e | 23.8 MtCO2e |

| Proportion of total transport emissions reduction reliant on mode shift from car to active and public transport | |||

| Measures to reduce emissions from Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGVs) | 1.8 MtCO2e | 2.8 MtCO2e | 4.9 MtCO2e |

| Proportion of total transport emissions reduction reliant on HGV decarbonisation |

It is worth putting these figures in context. The expected emissions reduction from mode shift from car to active and public transport between 2026 and 2040 is slightly larger (4% more) than the total expected emissions reduction from the waste management sector over the same period.

Co-benefits

The area where mode shift, particularly from car to walking, wheeling, and cycling, has a significant impact is in co-benefits.

The Climate Change Plan (page 16) states:

All co-benefits they [the University of Edinburgh] identify taken together could deliver over GBP6.3 billion worth of value to Scotland between 2025 to 2040, which is a per capita benefit of GBP1,150 over the 15-year period.

Of this, it predicts that health benefits flowing from increased physical activity from more walking, wheeling and cycling could produce GBP4 billion in co-benefits, that is 63.5% of total Climate Change Plan co-benefits - with additional benefits also accruing from noise reduction, reduced traffic congestion, and increased road safety.

The scale of the challenge

Achieving a significant reduction in the distance travelled by car, a substantial and sustained increase in trips made on foot or by bike, bus or train, and modal switch in the freight sector would represent a significant break with decades-long transport trends observed across the developed world.

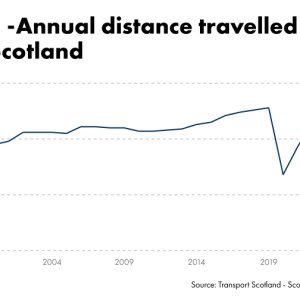

As shown in Chart 1 below, the distance driven by car has been on a consistent upward trend for the lifetime of the Scottish Parliament, except for a significant fall caused by pandemic related travel restrictions and subsequent changes in travel patterns. However, car travel has since resumed its upward trend.

This trend continued into 2025, with the latest provisional Department for Transport figures for October 2024 to September 2025[11] showing a further 0.4% increase in the distance travelled by car and taxi across Britain (Scottish figures are not yet available) - just 2.6% lower than the all-time high recorded in 2019. It seems likely that car travel in Scotland will mirror this wider 2024-25 increase.

At the same time, as shown in Chart 2 below, bus use has been on a downward trend for decades, with a significant pandemic related fall in patronage and a less pronounced rebound than car traffic.

ScotRail patronage had been slowly growing over the devolution period, mirroring a UK-wide growth in rail passenger numbers[12]. Again, ScotRail patronage has not rebounded post-pandemic to the same extent as car traffic.

In total, there were 517 million bus and rail trips in 1999-00 and 415 million in 2023-24, a fall of almost 20% - a period over which car mileage increased by more than 14%.

The one notable success in sustainable travel has been the increase in cycling over the devolution period. The distance travelled by bike increased by 69% between 1999 and 2023 (the latest year for which statistics are available) - from 238 million kilometres to 403 million.

However, a coronavirus related boom in cycling (which saw cyclists pedal 597 million kilometres in 2020, a 150% increase on 1999) has not been sustained - with the distance travelled by bike falling by 32% between 2020 and 2023.

Statistics on the distance covered on foot are not routinely collected, with Scotland-wide statistics[13] on walking indicating that there is likely to have been a modest increase as walking as a mode of transport over the devolution period.

Data from Scottish Transport Statistics on the share of the freight market for road and rail is reported in 'tonne-kilometres', a measure of freight transport effort calculated by multiplying the weight of goods carried (in tonnes) by the distance they were moved (in kilometres). In 2022-23 within Scotland, road transport accounted for 10,474 million tonne kilometres, while rail freight accounted for 387 million tonne kilometres - just 3.7% of that carried by road. There has been a significant fall in rail freight carriage within Scotland since the recent high point in 2010-11, when it accounted for 1,380 million tonne kilometres.

Much if this fall can be explained by the closure of large industrial sites dependent on minerals, coke, and coal normally supplied by rail, such as Longannet coal fired power station which closed in 2016.

Costs and who will pay them

The draft CCP only provides figures for 'total benefits' and 'net costs' for each sector and broad groupings of policies and proposals. It does not set out details of expected total costs associated with policies and proposals, or any breakdown of where these costs fall, principally individuals, businesses, or the taxpayer.

Modal shift from car to travel by foot, bike, bus, and rail will require significant and sustained capital investment by the Scottish Government and councils in improved pedestrian environments and the development of continuous, direct, and safe networks of bus and cycle lanes. It may also require ongoing revenue support for bus service provision and low-cost ticketing options.

However, the benefits accruing from increased activity and improved population health should ultimately lead to reduced NHS spending. These are not notional savings, academic research into the effect of investment in cycling infrastructure in the Netherlands[14] (where cycling accounts for around 28% of all trips[15]) has found that:

Cycling prevents about 6500 deaths each year, and Dutch people have half-a-year-longer life expectancy because of cycling. These health benefits correspond to more than 3% of the Dutch gross domestic product.

Our study confirmed that investments in bicycle-promoting policies (e.g., improved bicycle infrastructure and facilities) will likely yield a high cost-benefit ratio in the long term.

Improvements to the rail network to allow more freight services to run would require significant capital investment by the Scottish Government, costs could range from the millions of pounds for minor enhancements, such as more passing loops, to hundreds of millions for significant network enhancements or route re-openings. Similarly, new or expanded freight grants to encourage modal shift will require Scottish Government investment, as would any ongoing modal shift revenue support scheme.

Costs associated with the uptake of zero emission HGVs would largely fall to the private sector, but any requirement to speed the replacement of vehicles outside of regular fleet renewal would likely require government support. There is also the fact that zero emission HGVs are considerably more expensive than diesel equivalents and are expected to remain so for the forseeable future.

It is worth noting that small operators dominate the Scottish haulage industry.

In 2024 64% of Scottish licensed HGV operators had one or two vehicles, while 80% had one to five vehicles (Scottish Transport Statistics 2025, Table 1.10). Combine this disparate industry structure with the fact profit margins are notoriously low, access to finance difficult, and the average age of drivers is high (over 50 according to the Road Haulage Association) then it will clearly be a challenge to decarbonise this sector. More information is available in the 2024 UK Department for Transport sponsored study "Understanding the road freight market[16]".

Issues raised in the call for views

Respondents to the call for views that ran prior to the publication of the draft CCP, who commented on transport issues, were effectively unanimous in their views on the priorities for reducing car use and facilitating trips by foot, bike, and public transport, arguing that:

- A detailed plan setting out car use reduction goals and how these will be delivered is urgently required to deliver transport emissions reductions that cannot be delivered through electrification.

- Modal shift from car travel to public transport, walking and cycling can be delivered through the development of:

- a comprehensive, reliable, affordable, and accessible public transport network that provides a viable alternative to car travel for as many people as possible.

- safe, accessible, uninterrupted intra and inter urban walking and cycling networks, segregated from general traffic, to encourage walking, wheeling, and cycling for suitable trips.

- Travel demand management measures, such as road user charging, workplace parking levies, and reallocating road space to pedestrians, cyclists, and buses are a vital element in driving modal shift from car to public and active travel.

Issues raised in oral evidence

The Net-Zero, Energy and Transport Committee questioned a panel of academics and representatives of the bus and freight industry on the car use reduction, mode shift, and freight decarbonisation aspects of the draft CCP at its meeting of 6 January 2026[17], significant issues raised by witnesses during that meeting include:

- There was universal support for car use reduction targets, but these need to be backed up by robust, proven policies, budgets, and political leadership for there to be any chance of successful delivery.

- Modal shift from car use to walking, wheeling, cycling, and public transport cannot rely on "encouragement" alone, as such an approach has failed over the last 20 years.

Behaviour change requires both improving the alternatives to the car and making certain car trips less attractive.

- Behaviour change requires consistent long-term policy approaches, funding streams, infrastructure development, and social marketing.

- Some transport policy interventions listed in the CCP, such as concessionary fares, may have wider social benefits but do little to reduce GHG emissions.

- CCP policies for road freight decarbonisation do not consider issues around affordability, total cost of ownership, range, and the load carrying capacity of zero emission HGVs, which are commercially unviable for the vast majority of operators now and for the foreseeable future. Consideration should be given to the role that could be played by alternative fuels that can be used in existing diesel HGVs.

- While freight operators support modal shift from road to rail and water, commercial realities and the extent of rail and shipping networks mean road will remain the dominant mode. Modal shift can only ever play a relatively minor role.

- There is insufficient detail in the draft CCP to assess whether the policies and proposals are likely to deliver the stated outcomes.

There is a need for realistic, deliverable milestones and robust monitoring of car use reduction and modal shift.

Conclusion

There is strong support from transport stakeholders for the establishment of a new car use reduction target and policy, modal shift from car to walking, cycling, and public transport, and the decarbonisation of freight transport as set out in the draft CCP.

However, concerns have been raised about a lack of clarity on targets and modelling assumptions, and the lack of detailed information on policies, budgets, delivery mechanisms, governance, the commercial viability of proposals, and whether technology in some areas is sufficiently mature to deliver stated goals.

Alan Rehfisch

Senior Researcher (Transport and Planning), SPICe

Share this:

Like this:

Like Loading...References

- ^ draft Climate Change Plan update (www.gov.scot)

- ^ A Route Map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030 (www.transport.gov.scot)

- ^ Sustainable transport: reducing car use (audit.scot)

- ^ meeting of 23 April 2025 (www.parliament.scot)

- ^ Achieving Car Use Reduction in Scotland: A Renewed Policy Statement (www.transport.gov.scot)

- ^ data presented by the Climate Change Committee (www.theccc.org.uk)

- ^ Annexe 2, page 33 (www.gov.scot)

- ^ Bute House Agreement (www.gov.scot)

- ^ Sustainable travel: Reducing Car Use (audit.scot)

- ^ 2019-20 Programme for Government (www.gov.scot)

- ^ Department for Transport figures for October 2024 to September 2025 (www.gov.uk)

- ^ UK-wide growth in rail passenger numbers (app.powerbi.com)

- ^ Scotland-wide statistics (www.transport.gov.scot)

- ^ academic research into the effect of investment in cycling infrastructure in the Netherlands (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ for around 28% of all trips (english.kimnet.nl)

- ^ Understanding the road freight market (assets.publishing.service.gov.uk)

- ^ meeting of 6 January 2026 (www.parliament.scot)