Going the extra mile: Into the wilderness with Mazda’s rotary …

An icy road clinging to the remote, windswept mountains of Iceland’s northwest peninsula seems like a good place to talk about range anxiety. The sun is rapidly sinking towards the horizon, we’re several hours’ drive away from the nearest town and the battery indicator on the Mazda MX-30 R-EV is showing just 15 km of range remaining. This is emphatically not somewhere that you want to run out of charge.

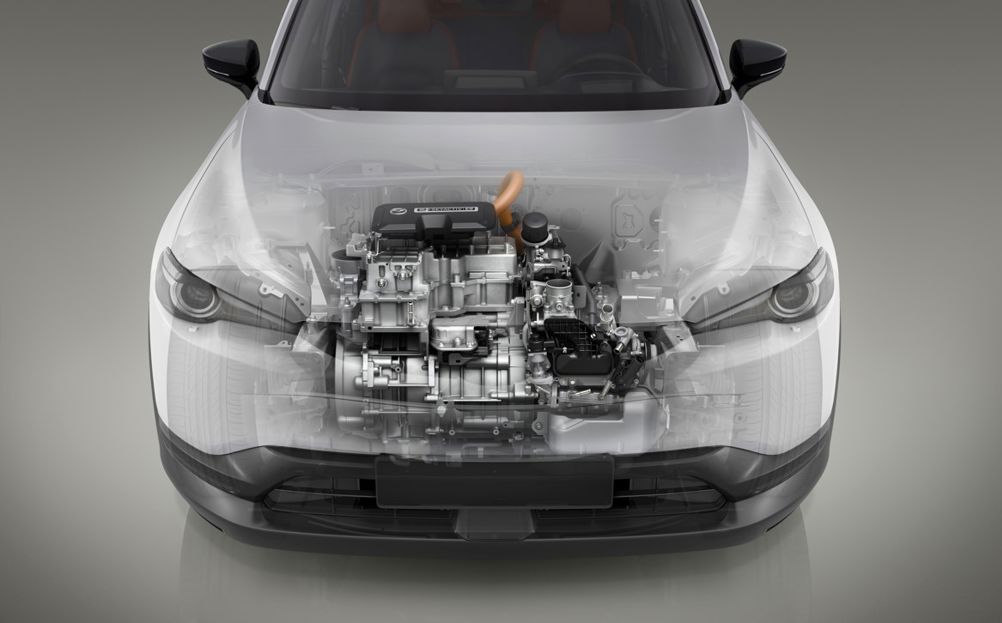

The rotary engine is back as a range extender generator in the electric-powered Mazda MX-30 - Mazda

The rotary engine is back as a range extender generator in the electric-powered Mazda MX-30 - Mazda

Fortunately, Mazda has a solution. Like the standard MX-30, the R-EV is electrically driven at all times, with a modestly-sized lithium ion battery that reduces the cost and environmental impact of manufacturing the powertrain. Mazda refers to this philosophy as ‘right-sizing’. It’s about providing the sort of range that most people need in day-to-day driving, rather than sizing the system to cope with the rare occasions when they might find themselves driving the length of the M1 or crossing the Icelandic wilderness.

At 17.8kWh, the battery in the R-EV is half the size of that in the standard MX-30, but it’s still good for a claimed 53 miles of range. For comparison, Mazda has analysed the data from its digital service records and says that the average daily mileage for a customer in the UK is just 26 miles.

But what about when you need to go further afield? In addition to DC rapid charging, the R-EV features a compact range extender system that charges the battery on the move using a petrol-driven rotary engine. It gives a combined range of over 400 miles with CO2 emissions of just 21g/km.

Those figures aren’t dissimilar to any number of plug-in hybrid models that have sprung up over the last few years, but Mazda has taken a fundamentally different approach to the design. Instead of pairing a fully-functioning traditional drivetrain with a separate electric motor, the tiny 830cc single-rotor engine in the R-EV acts purely as a generator, with no physical connection to the wheels. It sits under the bonnet, while a separate oil-cooled motor drives the front wheels. The whole assembly takes up roughly the same space as a typical four-cylinder engine.

Engine design

Mazda’s love affair with the Wankel rotary engine is well-documented. The company first experimented with the technology in 1961 as part of a joint R&D venture with German firm NSU. This led to the twin-rotor Mazda Cosmo, which was first unveiled in 1964 and went into full-scale production in 1967.

The rotary engine offered compact dimensions, smooth operation and a high specific output, but it was dogged with problems relating to rotor tip wear, oil burning, fuel consumption and emissions. Despite this, Mazda persevered with the concept right up to 2012, producing more than two million units in the end.

Part of the reason that Mazda has been able to revive the concept – despite the considerable challenges posed by modern emissions legislation – is that the new engine faces a very specific set of operating conditions. For a start, it’s only used on demand and spends much of its time dormant. When in use, the engine operates over a relatively narrow speed range (around 2,300 rpm to 4,500rpm) with no need for high speeds or aggressive transients. If the driver suddenly puts their foot down, it’s the battery that takes the strain.

Nonetheless, it’s taken a considerable amount of development work to meet the efficiency, durability and emissions targets for this all-new engine, according to Christian Schulze, director of technology research at Mazda’s European R&D centre.

“One of the most significant differences [compared to Mazda’s previous rotary engines] is the switch to direct fuel injection,” he told The Engineer. “This makes it possible to distribute the air-fuel mixture more effectively within the main combustion area, resulting in more efficient combustion, lower emissions and better fuel economy.”

Direct injection increases the cooling effect as the fuel evaporates during the compression phase. Likewise, exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) is used at low speeds and loads to reduce the combustion temperatures.

The tiny single rotor engine sits under the bonnet and has no physical connection to the wheels -

The tiny single rotor engine sits under the bonnet and has no physical connection to the wheels -

Careful work on the combustion chamber geometry has also increased charge motion, which leads to faster and more efficient flame propagation. Between these changes, Mazda has been able to increase the compression ratio from 10:1 in the old RX-8 engine to 11.9:1 – unusually high for a rotary engine.

Sealing the chamber under these conditions requires a considerable amount of pressure to be applied to the apex seals at the tip of the rotor. In order to reduce wear – the Achilles’ heel of traditional rotaries – the seals have been increased in thickness from 2.0 to 2.5mm.

The plating on the surface of the trochoid (the static housing that forms the outer wall of the chamber) has been revised to reduce material wear and frictional losses. Meanwhile, the side housings – now made from aluminium rather than steel, saving 15kg over the previous engine – are coated with a ceramic material using a high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) process. This reduces friction and wear, thereby reducing oil consumption and improving lubrication. Although a small amount of oil is still injected into the chamber, it’s claimed that the MX-30 R-EV will achieve the same sort of service intervals as a conventional reciprocating engine.

Into the wilderness

Out in the Highlands, it’s still diesel 4X4s that seem to rule the roads in Iceland. However, it was a very different story when we set off from Reykjavik in the morning, with Tesla Model 3s and Model Ys dominating the pre-dawn rush hour of one of the most EV-friendly cities in the world.

The MX-30 R-EV felt very much at home, delivering the characteristically smooth swell of torque that you get with an EV. Using the default powertrain mode, the engine stays off until the battery falls to 45 per cent charge – more than far enough to get us out of Reykjavik and into the stark volcanic landscape that makes up the southern portion of the island.

As we head north, the range extender cycles on and off, hovering at around 20km of electric range. On the move, it’s virtually impossible to detect over the whine of the studded winter tyres. It’s easier to pick out when stationary, with a faint whirring sound a bit like a distant air compressor, but it’s still quieter than a conventional engine. With the radio on, you’d struggle to hear it at all.

Within a few kilometres the vistas widen. Civilisation thins out to a handful of isolated farmhouses and characteristically Scandinavian churches with their tall, windswept spires. The landscape becomes more familiar in a way - not unlike the Scottish Highlands, but on a far bigger and emptier scale.

The MX-30 R-EV being put through its paces in the wilds of Iceland -

The MX-30 R-EV being put through its paces in the wilds of Iceland -

Two hours later we’re still driving through the same deserted landscape, having seen maybe four or five cars. Eventually, even the tarmac runs out and we end up on dark, volcanic gravel roads. The surface turns to ice as we head up into the hills and the snow patches become an unbroken blanket of white. It’s starkly beautiful outside, but reassuringly calm inside, with half a tank of petrol left to banish any residual range anxiety.

Granted, a conventional parallel plug-in hybrid would have achieved much the same thing. But all too often they leave you with the feeling that one half of the powertrain is an afterthought – either a token zero emissions capability to appease the legislators or a thrashy and unrefined combustion engine to extract some meaningful range from a vehicle that ultimately feels like it would prefer to be fully electric.

The series hybrid setup in the MX-30 feels more coherent. There’s no Jekyl and Hyde personality shift as one power source takes over from another. Unlike hybrid versions of some combustion engined cars, the boot space is unaffected by the addition of the range extender. And although Mazda hasn’t released a figure for the weight of the rotary engine, it’s safe to assume it’s less than that of a full-size reciprocating engine in a parallel hybrid.

Back in Reykjavik that evening, Schulze acknowledges that the range extender concept is aimed at the transition period we find ourselves in currently, where the charging infrastructure remains patchy in some areas, as does access to other low-carbon technologies, such as sustainable fuels. As stopgaps go, however, the MX-30 with its full-time electric drive and compact, lightweight range extender seems to make a lot of sense.