Bristol’s struggling public transport: what can it learn from France?

A modern tram travels along a narrow street in Bordeaux (credit: Per Karlsson / Alamy)

Back in the early 2000s, Bristol was one of more than 20 areas chosen by the then-Labour government for potential development of new tram networks. Had things gone ahead[1] as planned, with a proposed first line expected to complete around 2007, we might now have been deep into a new era of trams in the city region.

Instead, Bristol and South Gloucestershire councils failed to agree on the route and the scheme fell apart. Fifteen years on, with local public transport in crisis, the question of whether a tram system – or an underground metro – can offer a solution to Bristol’s transport problems remains.

Martin Garrett, the chair of local campaign group Transport for Greater Bristol (TfGB)[2], moved here from Nottingham, one city that successfully developed a new tram system during the New Labour years. “I was shocked at Bristol’s appalling public transport,” he says. “It made me a transport campaigner.”

After the failure of the Bristol tram project, the authorities began working on the much-criticised MetroBus[3] scheme – which TfGB was set up in 2008 to campaign against – and in favour of a tram network.

Bus users such as Mirela have been sharing their travel frustrations with the Cable (credit: Izzy de Wattripont)

Bus users such as Mirela have been sharing their travel frustrations with the Cable (credit: Izzy de Wattripont)

“As we predicted, MetroBus has not had much impact[4] [on Bristol’s public transport woes], with the possible exception of the service to UWE,” Garrett says.

Since 2017, the authorities have been looking again at ‘mass transit’[5] public transport options (see box), against a backdrop of mounting misery[6] for citizens reliant on buses. As the Cable has reported extensively, driver shortages, reduced timetables and routes being cut[7] have caused huge disruption to many people’s lives.

But the history of political conflict seems to be repeating itself.

Bristol’s mayor, Marvin Rees, favours an underground mass transit system. Meanwhile Dan Norris, the West of England ‘metro mayor’ believes that would be too expensive. The two men have clashed over a long-awaited feasibility study[8], which Norris’s West of England Combined Authority (WECA) has promised to publish[9] in October, after previously refusing to release it in full under freedom of information laws.

While recent British governments have provided little support for new trams and light rail, these services have been spreading rapidly across Europe. Since 1992, 30 French cities, many of them smaller than Bristol, have built hundreds of new lines.

Most carry trams, while some use driverless trains with rubber tyres. Some run entirely overground; others go underground in places. What can Bristol learn about its potential options from two contrasting examples – Rennes in Brittany and Bordeaux, Bristol’s twin city? And how justified is politicians’ rhetoric around these kinds of public transport offering a solution to notorious congestion – second only to London[10] in the UK – which Bristolians suffer every day?

The lowdown

After missing out on being part of the wave of UK tram network projects set up either side of the millenium, Bristol is re-evaluating its public transport options as it grapples with longstanding congestion issues and a worsening bus crisis.

The city’s mayor, Marvin Rees and his West of England ‘metro mayor’ counterpart Dan Norris have been at loggerheads as to whether an underground metro or a cheaper option to return trams to Bristol represents a better solution to the city’s travel woes.

With a feasibility study due to be published at last this autumn, the experience of regional French cities in developing new public transport networks over the past couple of decades offers some valuable context.

An alternative to gridlock

One recent European study[11] found that on average, a new network reduced congestion by 7% and travel times by 1%, but new lines or extensions made no difference. On its own, light rail does not reduce traffic volumes or carbon emissions by very much.

If cities want to do that, they also have to take more direct measures to restrict traffic. But, as illustrated by the heated debates around the East Bristol Liveable Neighbourhood[12], which aims to reduce traffic in St George, Redfield and Barton Hill, these can be highly controversial.

Rather, the main benefit is to provide an alternative to congested roads. In cities like Bristol, where population density is growing and there is no more land for roads or parking, people need alternative ways to move around. Trams and metros may also bring other, more surprising benefits – as some French cities have discovered.

A pre-feasibility study, commissioned by Bristol City Council, was published back in 2017. It surveyed the wide range of rapid transit available (see box).

Different public transport types explained

- Heavy metro: This is a heavy rail, high-capacity system typically used in larger cities, such as the London Underground or Paris Metro.

- Light rail: As its name suggests this is a lighter version of the metro. It may run overground but traffic is always separated, running under or over the tracks. It’s typically driverless, using steel wheels on steel rails. Examples include the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) and Tyne and Wear Metro.

- VAL: Standing for véhicule automatique léger, VAL form of driverless light rail running on rubber tyres used in France – in Rennes, Lille and Rouen – as well as some other European countries.

- Trams: Bristol’s report considered trams, which operate in UK cities including Manchester, Sheffield, Nottingham and Edinburgh, as a type of light rail. Trams generally operate in mixed environments, where traffic is separated from the lines but may cross them at traffic lights. Some lines run underground. Some cities are preparing to introduce driverless trams.

- Bus rapid transport (BRT): Some BRT networks – for instance in Curitiba, Brazil or on a smaller scale in Runcorn – are entirely separated from traffic and run like a rail network. Some, like Nantes, are mainly separated. Others, like Bristol’s Metrobus, have only limited separation. Driverless buses are being trialled in some places but so far, all BRTs use drivers.

The next stage was a full feasibility study, commissioned this time by WECA in 2018, with input from Bristol City Council. So far, WECA has only released an extract showing the estimated costs, so we don’t know much about the different route options. However, we know that there would be four lines, running north, east, southeast along the A4, and southwest.

The eastern route has been controversial in the past. Proposals in 2008 to run buses along the Bristol and Bath Railway Path prompted mass protests.

This time, cabinet member for transport Don Alexander confirmed to us, the eastern route would run along Church Road – illustrating a further problem: the constrained width of Bristol’s radial roads. Rees has claimed the alternatives to digging an underground would involve “closing Gloucester Road to all other traffic or knocking down the shops on one side of Church Road”[13].

This new study showed a wide range of costs, from £1.6 bn for a bus rapid transit network up to £18.3 bn for a steel-wheeled underground metro, excluding land purchase, demolitions and the tunnel boring machine (see box).

The cost of change

Rubber-tyred vehicles Steel-wheeled vehicles Overground option 1 £2,071 £2,254 Overground option 2 £2,019 £2,540 Underground £20,271 £23,893Estimated construction costs of four rapid transit lines, per adult in West of England (source: WECA)

The high estimated costs of the underground networks prompted Norris to answer simply “no”[14] when asked by the BBC if Bristol would be getting one, a comment criticised by Rees. He has argued that WECA’s report is flawed because it is based on a whole network – rather than just the necessary sections, such as in the city centre – being put underground, therefore inflating projected costs.

Neither Bristol City Council nor WECA responded to our requests for an interview, ahead of the feasibility study’s publication. But one officer who is working on other transport projects was willing to talk off the record.

“Marvin wants to have his cake and eat it. He wants to build a metro without upsetting drivers, and I don’t think that’s possible,” the officer said. “If we build above ground, we have to remove traffic lanes and parking spaces.

“You should see the trouble it takes just to remove one parking bay – it takes months,” they added. “That’s why Marvin wants to go underground, but that’s very expensive. I don’t think we’ll be able to afford very much tunnelling.”

The officer questioned where funds would come from, pointing out that the Nottingham-style levy on workplace parking – which has anyway now been dropped[15] – would not be enough.

“Could we put in a congestion charge?” they asked, noting that the council has “all the cameras for the Clean Air Zone”, which only applies to a minority of older vehicles. “But how would drivers react to that?”

The French advantage

The French cities that have invested heavily in new public transport start with an important advantage: a much wider local tax base. In 2017[16], French local authorities raised two-thirds of their income locally, whereas their British counterparts relied on national government for two-thirds of their income.

For public transport projects, the difference is even greater. Since 1973, French cities have been able to levy a transport tax on employers. They can save those revenues, or borrow against them, to fund infrastructure projects.

Since it began building tramlines 20 years ago, Bordeaux – which has a metro-area population of about one million – has increased its transport tax to 2% of the payroll costs of each employer. In all, 82% of the cost of its first three tramlines was financed locally. All run overground, using a specially developed ground-fed system to avoid overhead powerlines through the city’s historic areas.

The years of construction caused traffic jams and press criticism, with the city employing mediators to work with residents along the affected routes. As Bristol has found, any proposal to remove traffic or parking provokes opposition from shop owners. It’s often said that French cities have wider roads, and that’s true in some parts of Bordeaux, but not everywhere.

On some streets there is only room for the tramlines and pedestrians – no other traffic. Deliveries to shops are sometimes done from side streets, or over the pavements at certain times of day. In other places, traffic was removed from squares and boulevards.

Tramlines had a transformational impact on Bordeaux’s Place de la Comédie between 2001 (L) and 2011 (credit: Mairie de Bordeaux)

Tramlines had a transformational impact on Bordeaux’s Place de la Comédie between 2001 (L) and 2011 (credit: Mairie de Bordeaux)

The decision to build a tram network followed years of familiar political arguments, with a former mayor wanted to build an underground metro. Karine Mabillon, director of transport for Greater Bordeaux, says the eventual choice of a tram system was “mainly because of the ground conditions, full of holes and waterlogged, for which the technology of the time wasn’t well adapted”.

“Faced with growing demand for mobility, the plan was to create a network of tramlines, like a star linked by circular express buses, and to develop heavy rail for the longer journeys,” she adds.

The last part of that plan, a regional express rail network, is scheduled to be completed by 2028, along with extended networks of express buses and cycle routes.

Surprising results

Bordeaux now has four tramlines, nearly 50 miles in length. So what difference has all that investment made?

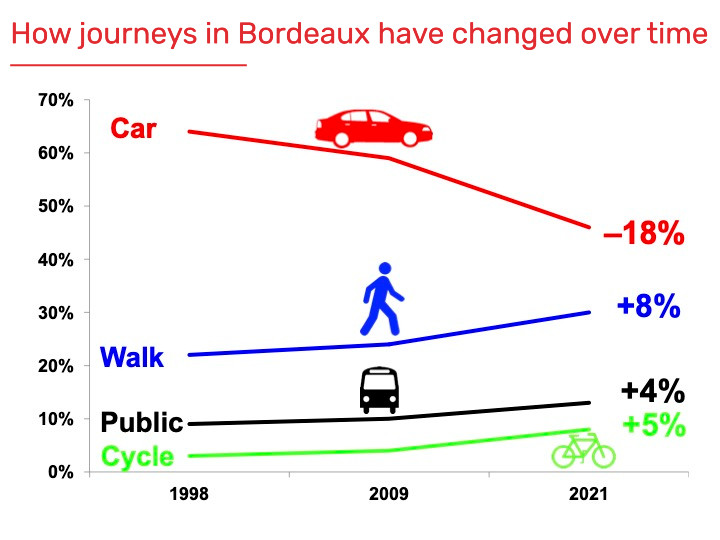

The statistics confirm Bordeaux’s trams are very well-used – three times the journeys per mile, compared with Manchester’s Metrolink trams – but the city’s travel surveys show some surprising results.

The share of car journeys has fallen because traffic levels have been fairly stable, while the growing population now travels more by other means. Public transport use has risen, but not dramatically.

Walking and cycling have increased more, because urban car ownership has fallen, and all that new traffic-free space may also have contributed. Several other French cities have followed similar trends.

But if all that sounds rosy, it’s not the full story. In recent years, there has been growing criticism of the trams. This is partly because they are often packed, but critics also describe them as slow and unreliable.

“The network is slow, on average, because it travels through some constrained areas and some very busy areas in the city centre – there’s not much we can do about that,” is Mamillon’s response. “There are probably too many stops, but that was what the councillors wanted at the time. It does suffer from breakdowns, but no more than any of the other French networks.”

In another significant twist to this story, the city has just commissioned a feasibility study into an underground metro. Why?

“We’ve now finished extending the tramlines,” Mabillon says. “Beyond a certain length, the journey distances become uncompetitive, and further extensions offer poor value for money. We’re starting at the beginning, looking again at those soil conditions.”

Planning for the long term

Although underground systems are more expensive, some French cities have built them at a reasonable cost. Rennes, a city half the size of Bristol, opened its first driverless VAL (véhicule automatique léger – or lightweight automatic vehicle) metro line in 2002, which has since been expanded and a second one added.

It carries three times the passengers per mile of Bordeaux’s tramlines, at nearly double the speed. Its cost per mile was nearly four times Bordeaux’s latest tramline, but less than a quarter of the underground estimates in the WECA feasibility study.

A driverless VAL train on Rennes Metro (credit: Arnaud Lubry, Rennes Ville and Métropole)

A driverless VAL train on Rennes Metro (credit: Arnaud Lubry, Rennes Ville and Métropole)

Why are transport projects so much more expensive in Britain? Back in 2010, a Treasury report[17] identified several reasons, which still seem relevant today. Their first one was “stop-start investment programmes”. As a result, contractors would invest for the next project but not for the longer term. Instead of sharing costs across projects, they are more likely to price each one as a one-off opportunity.

The comparison with France is clearest on that point. In any one year, several cities will be building or expanding tram or metro lines, supporting a domestic industry able to plan for the longer-term.

Engineers and contractors contacted by the Cable agreed with those points and added a long list of others. One wrote: “I worked with a major European contractor for several large infrastructure projects in the UK. They could not believe the amount of red tape and political interference over here.”

‘Bristol should revert to being a tram centre’

At a local level, the political landscape in Bristol is set to change once more in the coming months, with the city mayoral system on its way out to be replaced with a return to a committee-led arrangement. What would the Greens, who have overtaken the ruling Labour Party as the largest political grouping, do differently if they controlled the council?

Ed Plowden, who used to work in the council’s transport department and is now a Green councillor for Windmill Hill, talks about “complementary measures” around cycling, walking and parking restraint.

“On rapid transit, we would improve our existing bus network first – rolling out far more bus lanes on the main corridors that don’t have them and increasing the protected space on the ones that do,” Plowden says.

A bus in heavy traffic on Church Road, a likely route for trams in east Bristol (credit: Alexander Turner)

A bus in heavy traffic on Church Road, a likely route for trams in east Bristol (credit: Alexander Turner)

“Over time this could create the conditions for tramlines,” he adds. “But in the short term we need to work with what we have – we cannot afford to pin our hopes on plans for expensive projects which may not get funding, or disruptive heavy engineering or tunnelling.”

Transport campaigners partly agree. They support bus priority in some places, but want to see trams running as soon as possible.

“Most progressive comparable cities in both Britain and Europe have street-tram or rail-tram systems, including Birmingham, Nottingham, Sheffield, Newcastle, Edinburgh and soon Cardiff and Coventry,” says Gavin Smith, a retired transport planner and TfGB member. “Trams are high-capacity, frequent, reliable and close to zero emission. They are an attractive alternative for car owners, buses are none of those things.

Reporting on the stories that matter to you. Only with your support.

Join now [18]“Underground metros are ludicrously expensive,” Smith adds. “They have fewer stations, are less physically accessible and are less visible than trams.”

He suggests that a pilot tramline between Bristol and Bath would be a good way to start, possibly using the old railway line from Arnos Vale to Brislington. “Bristol City Centre should revert to its former status as a tram centre,” Smith says.

Once a city has built its first tram or metro line, expansion usually follows. That is true of all the cities mentioned in this article, and many others, so the recommendation, to start with something easier and get it built, is a good one. Some cities, such as Nice, have begun with an overground line and added a partly tunnelled line later.

The Cable will return to the subject of public transport when the feasibility study is published, but it is already clear that there are no easy alternatives.

In a growing city, doing nothing will make a bad situation worse. If we want trams or a metro, we need to figure out what mixture of traffic removal and new taxes or charges we are willing to accept.

Want more solutions for Bristol?

Reporting on solutions to Bristol’s biggest problems is expensive.

We won funding to explore how to make this important work viable for a local paper like the Cable! But to keep doing it, we need funding that won’t run out: monthly-paying membership.

Becoming a member, and encouraging others to join, means we can continue investigating solutions for Bristol into the future.

Find out more [19]The Future of Cities project is funded by the European Journalism Centre’s Solutions Journalism Accelerator, supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

References

- ^ gone ahead (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Transport for Greater Bristol (TfGB) (tfgb.org)

- ^ MetroBus (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ has not had much impact (www.bristolpost.co.uk)

- ^ ‘mass transit’ (www.bristol.gov.uk)

- ^ mounting misery (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ routes being cut (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ clashed over a long-awaited feasibility study (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ promised to publish (www.bristolpost.co.uk)

- ^ second only to London (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ One recent European study (diposit.ub.edu)

- ^ East Bristol Liveable Neighbourhood (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ “closing Gloucester Road to all other traffic or knocking down the shops on one side of Church Road” (thebristolmayor.com)

- ^ answer simply “no” (www.bristolpost.co.uk)

- ^ now been dropped (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ In 2017 (www.oecd.org)

- ^ a Treasury report (assets.publishing.service.gov.uk)

- ^ Join the Cable! (thebristolcable.org)

- ^ Find out more (thebristolcable.org)