13 Edinburgh transport projects which never made it, including …

The Edinburgh Airport Rail Link (EARL) would have involved building a tunnel under the main airport runway to bring trains to a station located underneath the terminal building. It was approved by the Scottish Parliament and scheduled to open in 2011. New sections of rail would be built to existing lines to allow regular trains from Glasgow, Fife and the north to call at the station. About £30m was spent on the scheme before MSPs agreed to scrap the scheme in 2007 - at the same time as they agreed to continue with the tram project.

Transport projects – whether it's trams[1], pedestrianisation[2] or low emission zones[3] – are almost always controversial.

But take a look at these ones which were abandoned before they were implemented. You might think some, like the hovercraft perhaps, were good ideas. Others now seem bizarre, not least the mind-blowing 1949 Abercombie plan,[4] which would have demolished swathes of the city centre to build an inner ring road.

In July 2007, Stagecoach ran a two-week trial of a hovercraft service between Portobello and Kirkcaldy. There were shuttle buses to the city centre and Leith. The service, called Forthfast, could carry 130 foot passengers at a time and proved popular with commuters and others. A total of 32,000 passengers made the 20-minute journey over the two weeks.Stagecoach was keen to carry the project forward and pledged to invest more than £10 million in two craft plus infrastructure, but the plans for a permanent route were sunk when Edinburgh City Council refused planning permission for a terminal. (Photo: Neil Hanna)

They offer a fascinating insight into the priorities of the past – sometimes the quite recent past – and how much thinking has changed.

This is the West Approach Road - originally known as the West Link Road - which opened in December 1974. But there was a much more ambitious and controversial scheme, the Western Relief Road, which would have served as a bypass for Corstorphine, running from the end of the M8, through Broomhouse and Stenhouse to connect with the West Approach Road. It was supported by the Tory administration on Lothian Regional Council but in 1986 they lost power to Labour who were pledged to scrap it. Alistair Darling, who became Labour's transport convener, later recalled: ""It was basically extending the M8 into Lothian Road. When we got elected, the contracts had been signed the day before the election and we ripped them up the day after, so it was never built." (Photo: Alan Ledgerwood)

The City of Edinburgh Rapid Transport (CERT) guided busway project was the forerunner of the tram scheme - buses with guide-wheels running on segregated concrete tracks but able to run on normal roads as well. The route was going to run from the airport to the city centre, but only a short stretch was built in the west of the city - from South Gyle Access to Stenhouse - before it was abandoned. Named "Fastlink" and built at a cost of £10m, it opened in 2004 but closed just five years later to make way for the trams.

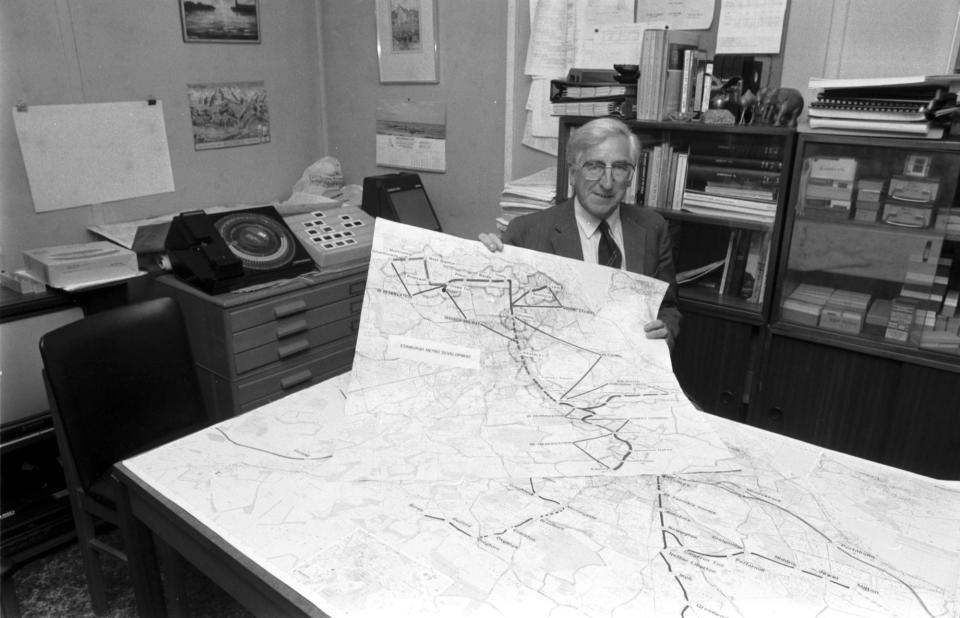

Proposals for an Edinbutgh metro date back to 1972, when Arnold Hendry, professor of civil engineering at Edinburgh University, put forward plans for a north-south, sub-surface light rail route, using the Scotland Street tunnel from Canonmills to the city centre and new tunnels south from there. In 1989, a wider £185m metro scheme, partially underground, was proposed, with an 11-mile north-south route through the city and plans for around 30 stations - each half a kilometre apart - with services running every five minutes. It was an ambitious project and it was eventually abandoned amid concerns about cost and practicality. (Photo: Alan Ledgerwood)

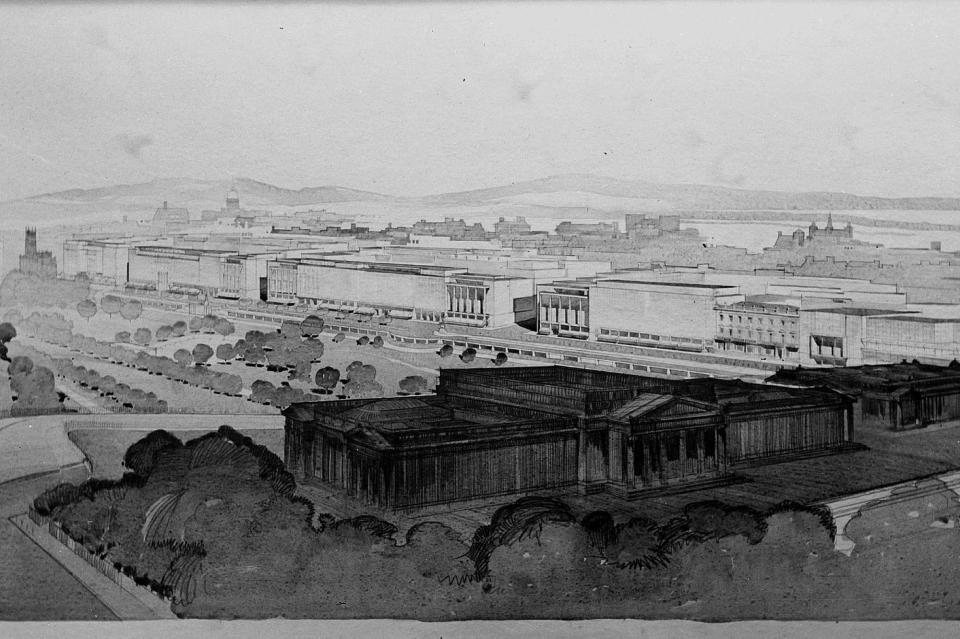

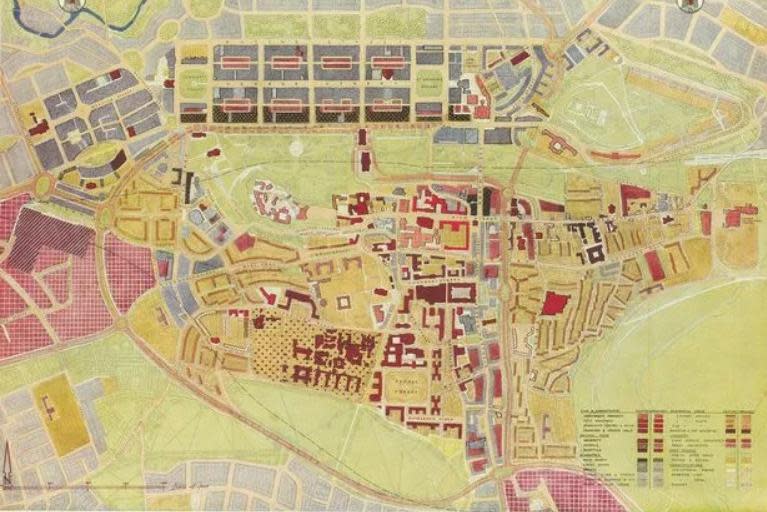

The 1949 Abercrombie plan for the redevelopment of Edinburgh would have changed the face of the Capital, including rebuilding Princes Street with a motorway running underneath as part of an inner ring route. It would have meant a "three tier" Princes Street - a local service road at ground level, a middle level proposed for car parking, and the motorway on the lowest level, with an open colonnade onto the gardens.

The 1949 Abercrombie plan for an inner ring route would have seen the new motorway run underneath Princes Street before linking to the top of Leith Walk, tunnelling under Calton Hill, heading through the Old Town and up through the Pleasance before cutting right across the Meadows, where it would have been elevated on concrete stilts.

This is Princes Street station at the West End being demolished in 1969 after closing four years earlier. But under the 1949 Abercrombie plan, it would have been kept and rebuilt as a multi-level station with the inner ring road running underneath it. Princes Street station would have operated inter-city services, while Waverley would have been downgraded to serve suburban lines only. (Photo: Denis Straughan)

A proposal for a congestion charge was put to a referendum in Edinburgh in February 2005 - and defeated. The plan was for motorists to pay a daily charge for driving in the city, raising up to £50m a year for investment in public transport and potentially paying for an extra tramline. There were to be two cordons, one around the city centre and one just inside the city bypass, both operating Monday-Friday. The inner cordon was going to apply from 7am to 6.30pm, while the outer one would only be in force during the morning rush hour, from 7am to 10am. Motorists would have been charged for crossing either cordon but would have paid only one charge per day even if they crossed the cordons several times. However, the proposal was rejected in the referendum by three to one - 45,965 in favour and 133,67 against. (Photo: Rob McDougall)

Edinburgh and Glasgow airports are only about 40 miles apart and 20 years ago there was a proposal to bulldoze them both and replace them with a single major airport for Central Scotland. Both existing airports were said to face problems in expanding to meet demand and it was argued a combined airport would offer better opportunities for hub-based operations. A similar idea had been floated as long ago as 1959. The new airport would have been built near Falkirk - it was jokingly dubbed Skinflats International - but in 2003 the UK government backed expansion of the existing airports instead. (Photo: Danny Lawson)

The Queensferry Crossing could have been a tunnel instead of a bridge. When it was decided a replacement crossing was needed for the Forth Road Bridge, there were calls for it to be made a tunnel rather than another bridge. It would probably have taken the form of an "immersed tube". Supporters argued such a solution would be cheaper, more environmentally friendly and could be delivered more quickly. But in December 2007, the then finance secretary John Swinney announced the Scottish Government had opted for a cable-stayed bridge.. Undated handout image issued by Transport Scotland of an artisit's impression of a new Forth replacement bridge alongside the current Forth bridge. PRESS ASSOCIATION Photo. Issue date: Thursday December 20, 2007. Plans to build a new road bridge across the Forth have been hailed as the biggest construction project for a generation by finance secretary John Swinney. Mr Swinney announced ministers had ruled out building a tunnel and were instead proposing to construct a new bridge to replace the existing Forth Road Bridge. See PA story SCOTLAND Bridge. Photo credit should read: Transport Scotland/PA Wire (Photo: Transport Scotland)

It sounds obscure, but the "Dalmeny chord" was a crucial stretch of rail which was never built. It would have linked the Edinburgh-Glasgow line to the Fife line and was a key part of the £1 billion Edinburgh-Glasgow rail improvement programme. It would have meant six trains an hour between the two cities, journey times cut to 35 minutes and trains calling at the new Edinburgh Gateway station (pictured) where passengers could switch to a tram to reach the airport. But in 2012 the budget was slashed to £650m, the Dalmeny chord was dropped, frequency remained at four trains an hour, journeys at 40 minutes and passengers from Glasgow heading for Edinburgh airport still had to travel to Haymarket and out again. Scottish Government Edinburgh Gateway Station to view it's progress as it nears completion.

It may seem unthinkable now, but it's not that long ago that the city council was looking into the idea of underground car parks in places like George Street or Charlotte Square (pictured) to help meet demand for parking. In 2007, a plan for a car park under Chambers Street got as far as more than a dozen firms bidding to build a £4.5m facility where cars would be lowered automatically to the subterranean parking spaces, but the proposal ran into legal problems about land ownership. Features 08/01/09 Charlotte Square. There are plans to build an underground car park beneath the park in the SquareEdinburgh New Town

References

- ^ trams (www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com)

- ^ pedestrianisation (www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com)

- ^ low emission zones (www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com)

- ^ Abercombie plan, (www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com)