Tech insider: Ferrari’s Le Mans winning 499P

Ferrari has won the 2023 Le Mans 24hrs, 50 year’s after it last competed for the overall in, and in doing so ended Toyota’s winning run.

Ferrari caused something of a stir when it announced it would return to the sharp end of sportscar racing, having not fielded a works prototype team since the 1973 312 PB. The company chose the Hypercar route, as is befitting of a marque with its history.

') } else { console.log ('nompuad'); document.write(' ') } // --> ') } else if (width >= 425) { console.log ('largescreen'); document.write(' ') } else { console.log ('nompuad'); document.write(' ') } // -->When the car was officially launched, John Elkann, Ferrari executive chairman, remarked. “The 499P sees us return to compete for outright victory in the WEC series. When we decided to commit to this project, we embarked on a path of innovation and development, faithful to our tradition that sees the track as the ideal terrain to push the boundaries of cutting-edge technological solutions, solutions that in time will be transferred to our road cars. We enter this challenge with humility, but conscious of a history that has taken us to over 20 world endurance titles and 9 overall victories at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.”

Based around an in-house developed and built carbon tub, the 499P combines the experience of Ferrari’s longstanding GT team with some of the engineering might its F1 operation brings to bear, particularly in hybrid system design and management and virtual car development.

According to Mauro Barbieri, Ferrari’s endurance racecar performance simulation and regulation manager, the development timeframe for the car was compressed, particularly the track testing element. “The on-track programme has been quite squeezed. In order to be able to join the championship in Sebring [2023],” he says. As a result, considerable effort was put into the virtual development program. “We did quite a lot of activity while designing the car and while producing the parts with the driving simulator to test different possibilities, different solutions, and I think we did quite some job on the virtual side.”

The team has access to both the DIL simulator used by the GT operation and also Ferrari’s older F1 simulator (replaced last year). By being able to work on setups in the sim, the focus of the six-month track test program could be on reliability. Barbieri says that this meant, “in terms of setup optimization, we didn’t push that much. And maybe on that side, we could, we could improve still a bit. And hopefully close the gap with the cars in the front.”

Giving more detail on the use of the DIL simulator, Barbieri explains. “With the driver in the loop simulator, we were trying to optimise the suspension, the aero maps that we were getting from the wind tunnel and trying to give development direction for the following sessions based on how the car was behaving at that time.”

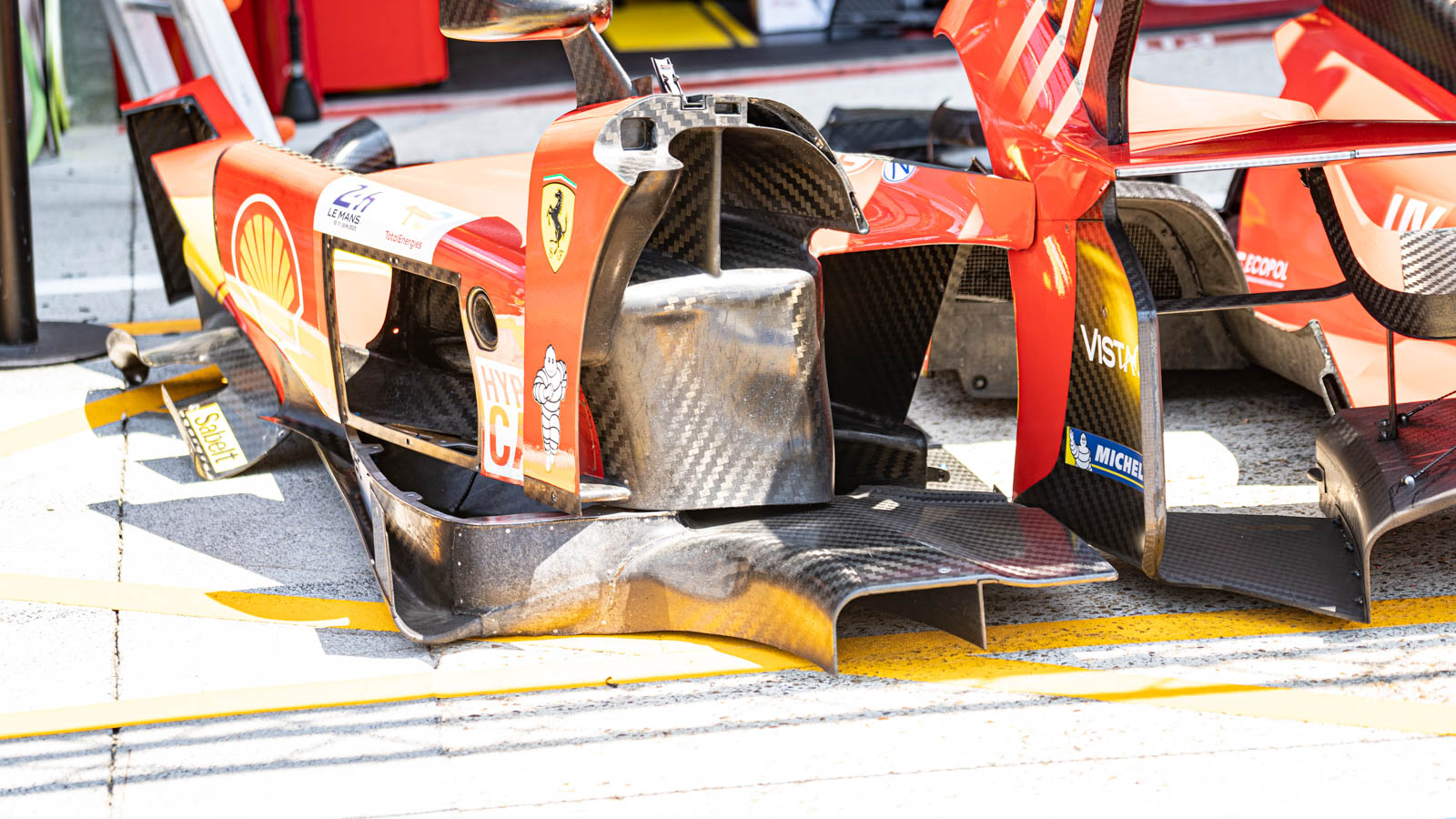

Aero/styling balance Though not going to the same extreme as Peugeot, the 499P was always going to carry a strong brand identity. “Anything that we produce in terms of racecars, the external design is always shared between the aerodynamic engineering and the style department, the design department of our company,” notes Barbieri. “That’s true for the LMH car but also for the GT3 cars as for the road cars, so we had quite a quite a few loops with between, let’s say, the aero engineers and the designers to make sure that we’re going to design a car that was not just fulfilling all the requirements, but that was also satisfying the eye.”

This, he adds, did not really place any limitation on the aerodynamic design thanks to the BoP regulations. “The downforce and drag limits, let’s say set by the technical regulations are not so difficult to achieved. And we also had some room to try and optimise the aero itself. For our needs I wouldn’t say that it has been in any way a constraint. It’s just been quite a few looping because the pure aerodynamic solution had to be slightly reviewed.”

Ferrari 499P

Ensuring there was sufficient flexibility withing the aero package to cover the various track types experienced over the WEC season was a prime consideration, particularly given that once homologation was complete, the package could not be changed. For this reason, says Barbieri. “We choose to go with the rear wing as an adjustable aero device to get to have a big span in terms of downforce level and drag level to try and be able to optimise the car at every single circuit.”

Ferrari 499P

He also points out that the rear wing is more useful than an adjustable front element, particularly when it comes to adjust setup throughout a race. “For example, one thing that you want to take into consideration is during Le Man is the transition from day to night, the temperature getting colder,” suggest Barbieri. “With the track going towards understeer, you might want the [adjustable]front wing to raise a bit the front downforce level. But then, if it rains, you normally want to go rewards with downforce to give the driver a bit more confidence. But maybe that’s not what you want to do, because if you reduce the front wing to move the downforce rewards, you might reduce the overall level of downforce. Normally the front wing is almost free in terms of drag. There are many aspects that you try to consider and probably you cannot tick all of the boxes, but we try to tick the ones that we believe were the most important.” Powertrain developmentThe 499P’s hybrid powertrain combines a mid-rear power unit with an electric motor powering the front axle. The latter, alongside the battery, being derived from solutions developed in Ferrari’s F1 program.

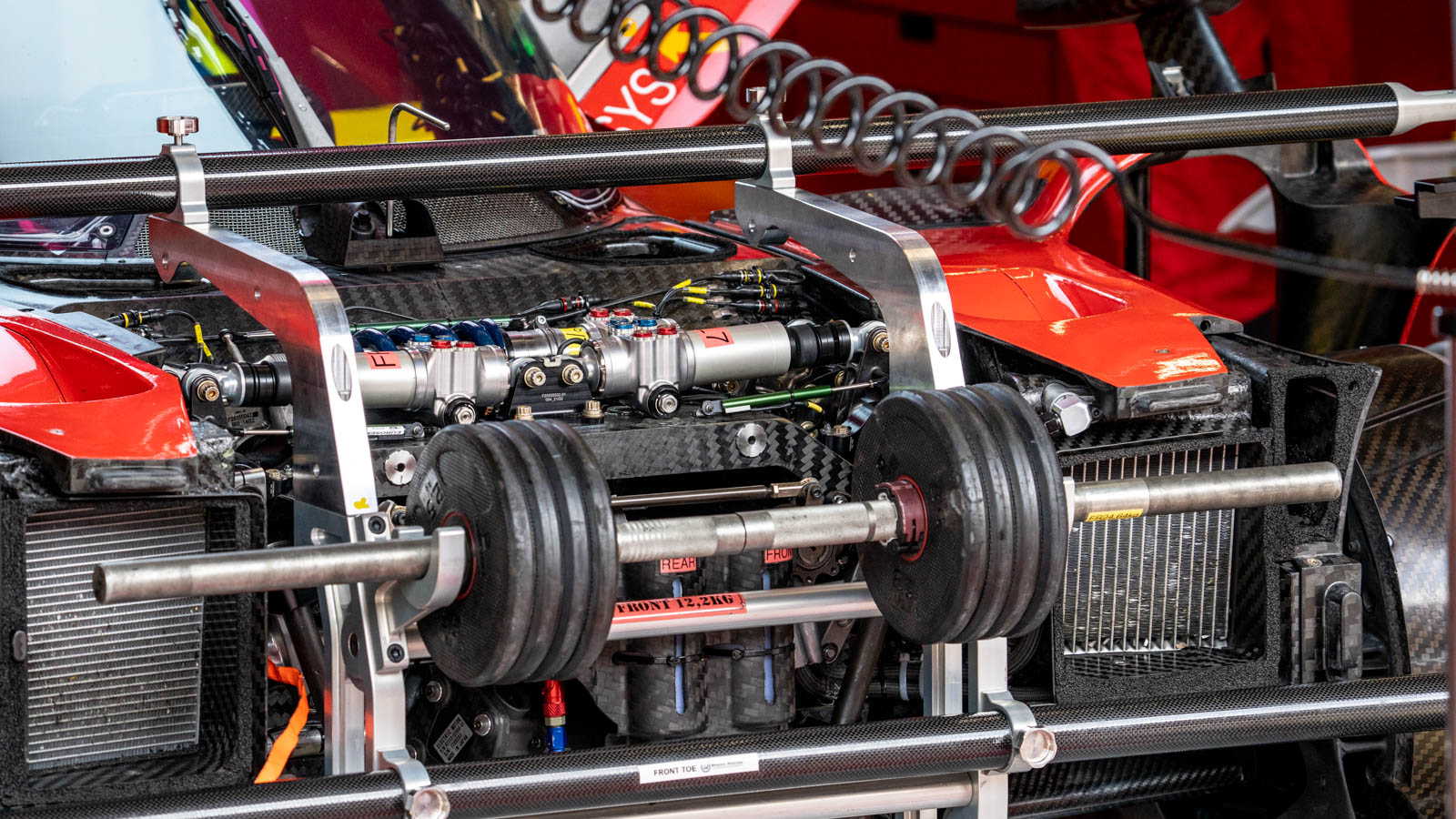

Powertrain developmentThe 499P’s hybrid powertrain combines a mid-rear power unit with an electric motor powering the front axle. The latter, alongside the battery, being derived from solutions developed in Ferrari’s F1 program.

The ICE has a maximum regulation-limited output to the wheels of 500 kW and is derived from the road-going twin-turbo V6 family found in Ferrari’s roadgoing cars and the 296 GT3 racecar. For prototype duties, the engine has undergone a thorough overhaul by Ferrari’s engineers, aimed both at prototype specific adaptions and reducing its overall weight. The key difference is that in the 499P, the engine is a load bearing element (in the GTE car it is mounted on a subframe).

Ferrari 499P suspension

The ERS system has a maximum power output of 200 kW and the front mounted MGU is equipped with a differential and recovers energy under braking. The battery pack, with a nominal voltage of 900V, benefits from Ferrari’s experience in F1, although it was purpose-built for the project. The 499P’s maximum power output is achieved either via a combination of hybrid and ICE power or, where needed, purely by the ICE, with drive delivered to the rear wheels via a seven-speed sequential gearbox.

Ferrari 499P

With plenty of customer experience on the sportscar side, Ferrari opted to work with Bosch on the engine and vehicle electronics systems, rather than with Magneti Marelli which is a technical partner on the F1 project.

F1 assistance It would be easy to assume that the sportscar team could rely heavily on the F1 department during the car’s development but given the intensity of competition in the latter series, there were limits to how much resource could be diverted. However, it was able to leverage some of the F1 outfits advanced, in-house developed tools. “With collaboration with the F1 team, let’s say we have separate departments. But this does doesn’t mean that we don’t share a lot of things in terms of software, in terms of know how, in terms of exchanging potential solutions in the car,” observes Barbieri. “From the outside, it might look like we’re not sharing that much. But in the end, we are the same company, the same family.”